London House University

- By Joe Alterman

- •

- 22 Jun, 2018

- •

Millennial Pianist Joe Alterman opens for the greats!

I’ll never forget the evening I opened for Hiromi at New York’s Blue Note Jazz Club. One of my favorite pianists, Ahmad Jamal, was in the audience, and it was the first time I performed for one of my heroes. It was exciting that he was there, listening intently to my set, but I spent nearly the entire performance in a state of crippling anxiety. For much of the weeks that followed, I felt embarrassed, shattered and confused. I had let - or, more accurately, I hadn’t been able to keep - my fear from getting in the way of the music which had, in my eyes, ruined the evening’s performance.

As the months passed and I reflected more on what exactly had happened that night, I eventually found strength in that moment and felt ready when I was asked to open one evening for another hero, Les McCann, also at the Blue Note. I was sound-checking when he entered the club. He approached the stage and quickly asked me to play him some blues. While I was worried about what I, a white, Jewish millennial could offer Les, one of the greatest blues players ever, I did my best, trying not to let fear enter my mind. After a minute or two, Les said, “Amen,” and I breathed a sigh of relief. When I finished playing, Les asked my name.

“Joe Alterman,” I said.

“Alterman,” he said, before asking, “You a Rabbi?”

“No,” I told him, through my laughter, “but I am a…”

“Hebrew?”, he interrupted.

Through my laughter again: “Yeah, I guess you could call me a Hebrew.”

“Well, from now on, you’re my He-bro.” And that was the start of a beautiful friendship.

I certainly felt more confident after that experience, but, while things had gone well with Les, I soon attributed that to luck, not skill; I still noticed that anxiety pop up whenever I spotted one of my musical heroes in the audience.

A few months later I was asked to open for another one of my heroes, Ramsey Lewis, again at the Blue Note. I remember the look my bassist gave me during the performance, which told me that Ramsey was standing right behind me watching us, but on this occasion, I found the nerves stimulating. By this point, I had realized that if I focused on performing for the audience as a whole, instead of to the one person in it who I really wanted to impress, I’ll, for the most part, be myself throughout. I spent some time with Ramsey after the set and he kindly gave me his email address before leaving. Little did I know at the time, but this would be the start of another beautiful friendship.

I opened for Ramsey again a few months later and this time we spent much of his set break chatting in his dressing room. It was here that he first told me all about playing opposite Oscar Peterson at Chicago’s London House in the 1960's where, as London House’s then-intermission pianist, he would play opposite Peterson and his trio every night for three weeks at a time, four sets a night, twice each year. I asked him if he ever got nervous performing in front of Peterson. “No,” he told me. “I only knew that I could do what I could do the best that I could do it, so I did it. You know?”

A-ha!

It wasn’t long before Les told me, “There's only two things in this life: love and fear. There's no jealousy, hate, etc. It all falls under one of those two categories. Everything we do here on Earth is a challenge to fear or to love,” and that advice, along with Ramsey’s, gave me both the confidence and understanding I needed to move forward, fear-less.

As I reflected on this later, I started to wonder: if I was getting so much out of these one-night opening acts, which only occurred a few times a year, the thought of how much Ramsey could’ve learned from spending so much time around Oscar Peterson and so many other greats was unfathomable.

As I got to know both Ramsey and Les better, it became apparent to me just how educational and, in many ways, formative, their time at London House had been. The more I spoke with and/or read (either about or interviews with) past London House-performers, the more I found this to be so. And, like jazz music, an oral tradition in itself, these findings weren’t simply stories; there was much within that I learned from myself, lessons I find important to save for future generations, too.

Softly, As In A Morning Sunrise

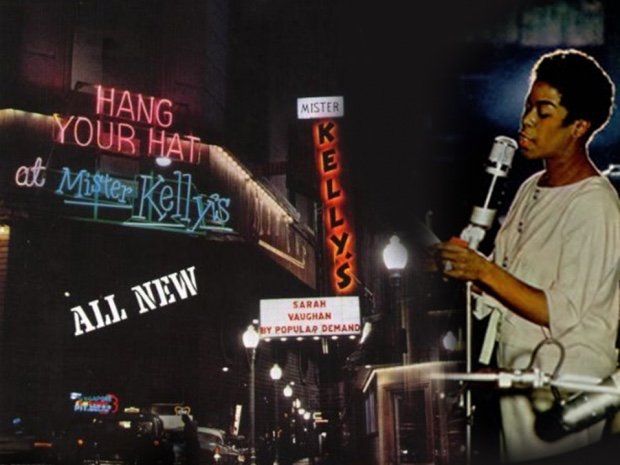

Owned by brothers George and Oscar Marienthal since 1946, London House began presenting jazz (piano trios in particular) in 1955, and it remained one of the city’s most popular jazz rooms until it’s closing in 1975. Located at the corner of Wacker Drive and Michigan Avenue, there was a big sign out front of London House that read, “Make a date with a steak tonight”, and, under that, “Now appearing”, which is where you’d see name of pianists like Erroll Garner, Teddy Wilson, Marian McPartland, George Shearing, Barbara Carroll, and Oscar Peterson, each of whom would be booked at the club twice yearly for three weeks at a time.

“It was like going to class,” Ramsey told me. “They could very well have called London House ‘London House University’ because there was something about everyone who played there, both their playing and personality, that I learned from.” He then added, “The London House audience was a school within itself, too.”

In addition to being a popular destination for live music, London House was a steakhouse famous for its food. (As Les recalls, “The food at London House was something my memory shall never forget.”) This, mixed with the fact that London House was located in “The Loop,” Chicago’s business district, meant that it often drew businessmen simply looking for that after-work drink, resulting in, often times, a noisy London House which, while often frustrating for the performers at the time, became a prime learning opportunity.

Pianist Judy Roberts, who worked as an intermission pianist at London House from approximately 1968 to 1972, explained her schooling in this arena as well. She recalls being fired during her first month at London House for how she dealt with one particularly loud talker: “I jumped off the piano bench and ran off the stage. I grabbed the guy by the neck and started shaking him.” Luckily, George Marienthal liked her enough to dismiss the incident and her for only two days. When she returned, she learned a subtler way to deal with loud-talkers by watching iconic pros like George Shearing.

She recalls one evening when Shearing was performing to a hushed crowd, save for one loud-talker who was seated near the stage. Judy remembers watching as the attentive crowd grew frustrated, pointing out that, “while you did hear the music, you also heard this rising level of ‘shh’.” Finally, Shearing stopped playing, picked up the microphone and said to the audience, “I’m playing as softly as I can.”

Judy watched as the entire audience cracked up, and the loud-talker finally quieted down after realizing, through Shearing’s use of humor, that he was the only one talking.

One of Shearing’s longtime drummers, Rusty Jones (who Shearing met at London House during Jones’ tenure as Judy’s drummer), recalled a similar incident when someone dropped a glass and its crash caused a loud interruption. Shearing, the same guy who once replied “not yet” when an interviewer asked if he’d been blind all his life, said to the audience, ”We must be in Scotland. I just heard Glasgow.” Jones also recalled Shearing dealing with interruptions from the traffic outside. Similar to Erroll Garner, who, bassist Eddie Calhoun, in James Doran’s The Most Happy Piano, recalled mimicking, on London House’s piano, the exact sound of crashing plates, Jones recalled Shearing mimicking on that same piano the note being honked on the horn of the car outside of the London House.

Ramsey remembers watching Shearing successfully quiet audiences by playing increasingly soft. He even recalls times when Shearing’s playing gradually became so soft that, eventually, he’d only be mimicking playing the piano. “So he’s sitting there looking like he’s playing but all the audience is hearing is themselves. And all of a sudden, everyone got quiet.”

While many would assume that the initial natural instinct of most, when trying to quiet an audience, would be to play louder, learning that the opposite is actually so is an important moment in one’s musical upbringing (especially pianists). As Judy explained, “Seeing what they do; not just how great they play, but how they present it…was the greatest lesson of all.”

Another London House intermission pianist, Larry Novak (whose London House piano rivalry Oscar Peterson remembered in A Jazz Odyssey, recalling one evening when Novak’s trio played “four tunes we considered ours” and, even though “I am sure it was done with no malice…I decided to throw the piano battle into full gear… I launched the Trio into a set that exactly paralleled Larry’s, tune for tune.”) recalled a time when, despite Shearing’s best efforts to quiet an audience, it didn’t work. “He started to play, and he played one song, and he stopped, and he said, ‘If the tone doesn’t quiet down, I’ll have to stop, because the people who came to listen can’t hear.’ So he started again another song. The volume went up and so did he.”

Ramsey pointed out another important thing he learned as part of his London House education: the art of pacing one’s set. He explained to me that there would be noise in the room during the first part of the set, because that’s when the waiters and waitresses would be delivering food and drinks. “The challenge”, Ramsey said, “was how to maintain my frame of mind and overcome until the room was quiet.”

Regardless of whenever the room became quiet, there were always things to be mindful of. “There were things to be learned from everyone,” Ramsey explained. “There were people there who had finished their food and were sitting there very quietly listening, but there were also those who were just trying to get through with their dinner, desert and coffee. You had to be mindful of them all, which taught me how to pace my set. Often, before London House, I would do a setlist of just a bunch of songs I wanted to play during that set, but at London House, because of the delivering of food and drinks the first part of the set, I started figuring out what to play when, depending on how the audience felt.”

Help me solve the mystery of it, teach me tonight

However, and perhaps most importantly, London House became the vehicle for many to learn lessons that, like the ultimate goal of the practice of the music itself, helped one further discover oneself.

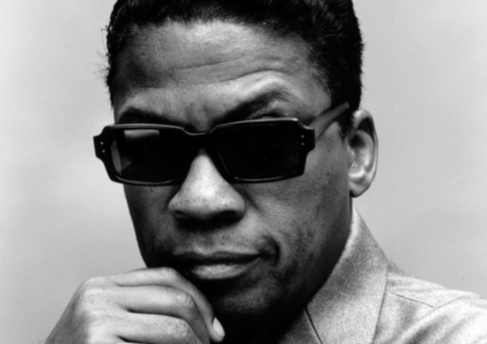

“London House was one of the best places I ever played,” Les told me. “It was an eye-opening place for me…I had a major learning experience there.”That experience took place one evening at the club when, just about to go on stage, Les saw Oscar Peterson walk in the door, which made him very nervous.

“I went over to say hello to him and I sat down for a second to talk to him and told him, ‘Wow, you’re one of my favorites.’

“That’s beautiful,’ Oscar said. ‘I’m glad to be here.’

‘I don’t know if I can play in front of you,’ I told Oscar. ‘I’m so nervous, I can’t believe it.’

“Oscar looked at me and said, ‘I didn’t come here to hear me. I came here to hear you. So you don’t have to be nervous. Do what you do. I love what you do.’

”He was telling me to be myself,” Les explained. “And that calmed me for the rest of my life. It was a moment of saying that I never have to fear what I do myself again…Without that experience, I’d have probably been fearful for some time longer. I’d’ve had to learn that anyway, eventually, but that’s what I learned on that spot and at that moment. I never looked back after that, either.”

Which sounded vaguely familiar to me…

But, really, Les never looked back after London House. London House represented an important milestone and stepping stone in Les’ career. “London House lifted me up to a different level of where I could play,” he said. “Before London House, I played in dives that had terrible-out of-tune pianos, places where there’d be bullet holes in the windows, places that would be packed with people, everybody talking at the same time. Playing the London House was a major step up for me. Once I played the London House it was like I was a real performer, a real pianist. It was like going from the basement to the penthouse. After London House, I never went back to the dives anymore.”

While London House became an important stepping stone in Ramsey’s career too, for him, a native Chicagoan, London House had long been a destination, a dream.

“As a youngster,” Ramsey told me, “I used to take the bus to my piano lessons, and I still recall seeing the sign out front of London House as the bus would cross the Wabash Bridge. I remember looking at it and thinking to myself, ‘Wow. That place must be really great.’ And it was…”

Just as Les’ time with Oscar Peterson at the club had been deeply impressionable, so had been Ramsey’s. Besides the obvious musical lessons one must have learned from being around that much great music (remember, he saw Oscar every night for three weeks at a time, four sets a night, twice each year for quite a few years), deeply impressionable on Ramsey was the time he got to spend with Peterson off-stage at London House, where he got to ask him questions and watch him interact with his fans and other pianists.

“I noticed that he would take as much time as he could to talk to piano players, no matter who they were. It didn’t matter if he didn’t know them or not, but, if he had the time, he would offer whatever he could, always in a calm and straightforward manner. To be one of the greatest piano players of all-time, and acknowledged by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Lester Young as such, and then to be humble enough to stop and talk to other piano players without any ego involved at all, was an incredible thing to witness.”

Ramsey recalled an especially impressionable day when, after asking Oscar “how do you do what you do?”, Oscar invited Ramsey to his hotel for a piano lesson the following day. The lesson: “He told me to play for the next 10 minutes using only the notes from middle C to the F an octave and a half above. He told me to be creative, not to repeat myself and to make it swing. It was very difficult for me, but he did it with incredible ease.”

It was apparent to me that Ramsey learned a lot from this meeting, but almost as important as the lesson itself was the fact that Peterson had taken the time out of his day to do that. “It was one of the moments that made him endearing to me,” Ramsey said.

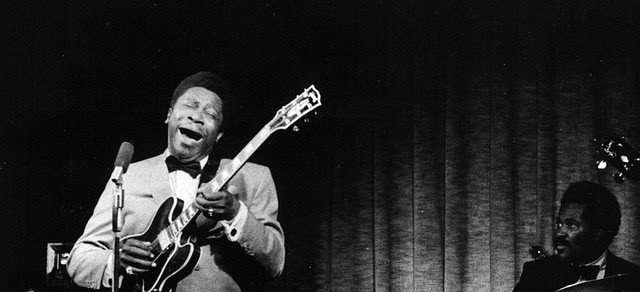

Ramsey also recalled learning a lot about respect for the music from Peterson. “We wear suits and ties because we respect what jazz is all about. That’s showing respect not only for the music, but also for what you are about to play. And plus, all the masters who came before us wore suits and ties. You know, back in the day, they were grateful that people came to see them, and part of wearing the suit and tie was part of that thanking them for coming. We respect the music, and we respect the people who come to see and hear the music.”

Ramsey also told me that, “At one point, there was another house pianist at the London House working opposite him, trying to outplay Oscar in Oscar’s style. Watching how that went down was quite instructive, too.”

That pianist, Eddie Higgins, wrote about the experience in February 1985’s JazzLetter:

As I attempted to sneak past him into the bar, he reached out and grabbed my arm.

"I want to talk to you," he said in a grim tone of voice.

I followed him out into the lobby of the building, which of course was deserted at that time of night. He backed me up against the wall and started poking a forefinger into my chest. It still hurts when I think about it.

"What the hell was that set all about?" he said.

I started a feeble justification, but he cut me off. "Bullshit! If you couldn't play, you wouldn't be here. If I ever hear you play another dumb-ass set like that, I'm going to come up there personally and break your arm! You not only embarrassed Richard and Marshall, you embarrassed me in front of my friends, just when I had been telling them how proud I am of you, and how great you play.

"I know we're having a good night, but there are plenty of nights when you guys put the heat on us, and if you don't believe me, ask Ray and Ed. We walk in the door, and you're smoking up there, and we look at each other and say, ‘Oh oh, no coasting on the first set tonight!' So just remember one thing, Mr. Higgins, when you go up there to play, don't compare yourself to me or anyone else. You play your music your way, and play it the best you have in you, every set, every night. That's called professionalism." And he turned and walked back into the club without a further word.

I've never forgotten that night for two reasons. It was excellent advice from someone I admired and respected tremendously. And it showed that he cared about me deeply.

London House was obviously a very special place. It wasn’t just another place to play.

Perhaps Judy sums up the importance of her time there best, speaking as she makes the sign of the cross on her chest: “I’m Jewish, but I’m going like this because that’s how much it meant to me.” She continued, “Imagine getting to see and hear George Shearing two sets per night for three weeks, up-close and personal, and then becoming friends, and then have him show me how to do his famous ‘block-chords’! As a teenager, this was absolute heaven. And then there were all the times with Cannonball Adderley, Oscar Peterson, The Three Sounds, Marian McPartland, and many, many more. Nothing can take the place of your eyes and your ears being given the opportunity to absorb the truth in real-time!”

The fundamental things apply as time goes by…

While, at times, I’ve wished that I had said to Ahmad Jamal what Les had said to Oscar Peterson before the start of my performance that day, I’m now glad that everything happened as it did. It took failing in front of Ahmad Jamal to eventually learn the most important lesson that I have: to be confident in what you can do well, to play not what you think someone else wants to hear, but to play the things that make you both happy and you.

There’s a lot to learn from these London House stories. I find it both ironic and fitting that, just as the greatest thing one could’ve learned from their time at London House was to be oneself, I, in reading these stories and identifying so much with everything learned at London House, feel further encouraged that my job as a musician is to embrace my self too. I find comfort in knowing that it doesn’t matter to which generation one belongs; every musician, at some point or another, will have to learn the same lessons, and the ones learned at London House - and the ways in which they were presented - are lessons I will continue to learn from and certainly share with musicians younger than myself.

As the jazz tradition continues through time, and new students continue to learn from older masters, we must remain grateful, not only for the current venues that give us the opportunity to learn these lessons, but also for places like London House for existing and paving the way - in so many ways - for the circle to remain unbroken.

And I must try out Shearing’s “softly” line sometime…

A native of Atlanta, Georgia, Joe Alterman studied music at New York University, where he received both his Bachelor's and Master's degrees in Jazz Piano Performance. In addition to performances with Houston Person, Les McCann and his own trio, among others, Alterman has performed at many world renowned venues including the Kennedy Center, Lincoln Center, Birdland and New York’s Blue Note, where Alterman has opened, many times, for Ramsey Lewis. Only 29 years old, Alterman has released four critically-acclaimed albums, his most recent being 2017’s “Comin’ Home To You”. He was profiled three times by iconic journalist Nat Hentoff and was the subject of Hentoff’s very last piece on music in March 2016. Dick Cavett has referred to Alterman as “one fine, first class entertainer” and Ramsey Lewis has called Alterman “an inspiration to me” and his piano playing “a joy to behold”.

For more information, please visit www.joealtermanmusic.com

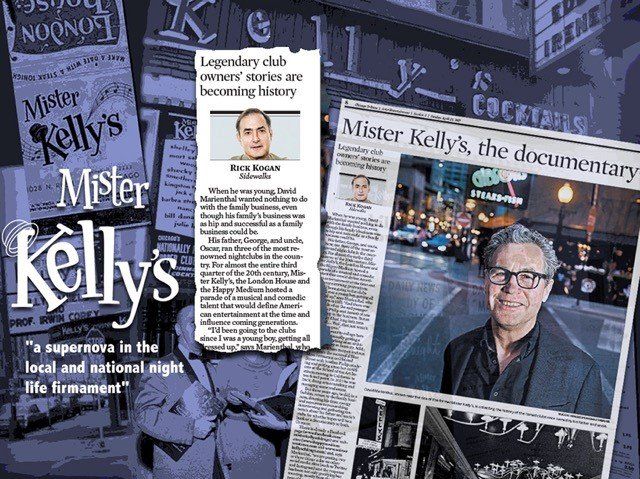

When he was young, David Marienthal wanted nothing to do with the family business, even though his family's business was as hip and successful as a family business could be.

His father, George, and uncle, Oscar, ran three of the most renowned nightclubs in the country. For almost the entire third quarter of the 20th century, Mister Kelly's, the London House and the Happy Medium hosted a parade of a musical and comedic talent that would define American entertainment at the time and influence coming generations.

"I'd been going to the clubs since I was a young boy, getting all dressed up," says Marienthal, who was born in 1951. "And there was some talk of us (he and younger brothers Philip and James) of one day getting in the business. But as a teenager I had long hair, torn jeans and …. Well, that just wasn't going to happen."

So off he went to college here and there, eventually getting a degree and working as an architect and builder in Sante Fe, N.M.; coming back here to open and run for 17 years the successful Blue Mesa restaurant on Halsted Street with brother Philip; studying and getting a teacher certificate at the School of the Art Institute; moving to California to teach and paint. In 2010 he was back, doing arts consulting and managing some real estate.

But three years ago, he did, in a fashion, return to the family business, devoting his time, energy and resources to researching, interviewing and gathering materials about his father and uncle's clubs for what he hopes will be a book or a documentary or both. Or more.

There is already a Facebook page ( www.facebook.com/misterkellyschicago ) and websites ( www.happymediumventures.com and www.misterkellyschicago.com ) and, says Marienthal, "we are posting two or three things a day on other social media sites (such as Twitter and Instagram) and the response has been not only gratifying but amazing, mostly from the 18-35 year old crowd."

This is how he puts a possible TV series — already with a script being pitched to producers — on his website:

Join us to support the legacy of Mister Kelly's and the documentary film being produced by David Marienthal with WTTW Chicago Public Media, directed by Philip Koch.

This two-act concert features Kimberly Gordon, Sophie Grimm, Lynne Jordan, Frieda Lee, LaShera Moore, Daryl Nitz, Jeannie Tanner, and Ellen Winters. Musical direction by Andrew Blendermann, with Joe Policastro on bass, Phil Gratteau on drums. Special guest performance by a Chicago high school student protege from ChiArts.

Happy Medium Ventures and Daryl Nitz Entertainment present:

Ella Live at Mister Kelly's: a benefit performance and preview for the documentary film, “Mister Kelly’s: Wasn’t It a Time?”

Monday, January 29, 2018

City Winery Chicago at 1200 W. Randolph Street, Chicago, IL 60607

$25-$40

For tickets go to Ella at Mister Kelly’s

Ella Live at Mr. Kelly's

On August 10, 1958, Ella Fitzgerald recorded her “Live at Mister Kelly’s” LP. In 2007 the concert was remastered and re-released in its entirety, including the early and late sets. This Ella centennial celebration concert presents the entire concert, without song duplication, of both sets. Featuring such songs as "Nice Work If You Can Get It," "The Lady Is a Tramp," "Summertime," "Witchcraft," "Come Rain or Come Shine," "Stardust," and many more from the classic American songbook of Gershwin, Rodgers & Hart, Porter, and others. Featuring Sophie Grimm, Lynne Jordan, Frieda Lee, Liz Mandeville, LaShera Moore, Daryl Nitz, Alina Taber, and Ellen Winters. Musical direction by Andrew Blendermann, with Joe Policastro on bass, Phil Gratteau on drums.

Mister Kelly’s: Wasn’t It a Time

Mister Kelly’s Once called a “supernova in the local and national night life firmament,” the legendary Mister Kelly’s illuminated legendary Chicago’s Rush Street, and the entire country, by launching talent like Barbra Streisand, Woody Allen, Bette Midler, Herbie Hancock, and Richard Pryor. It’s visionary owners George and Oscar Marienthal smashed color and gender barriers to put fresh, irreverent voices on stage and transform entertainment, as America knew it in the 50s, 60s, and ’70s.

Now, with the club long gone, and its star talent reaching its golden years, George’s son David, goes on a quest to collect the memories of the clubs before they are lost. Celebrity interviews now include Bob Newhart, the Smothers Brothers, Dick Gregory, Lainie Kazan, Dick Cavett, Shecky Greene and Ramsey Lewis. Interviews with dozens of local musicians, staff, family, and patrons provide a delightful balance with engaging stories, rich with vintage detail. Discussions are underway to interview Woody Allen, Lilly Tomlin, Bette Midler, Barbara Streisand, Steve Martin and others.

The film will portray through interviews, live footage, photos, music, and song, the most beloved and famous talent of our time at the decisive moments when they showed up, dug deep, and broke in. How do you change the world with a laugh and a song? Find out in a film that documents the rise and fall of one of American entertainment's great proving grounds.

Check out the hot sizzle reel and read Rick Kogan’s story in the Chicago Tribune and the links below for more about this exciting new film.

• Chicago Tribune Story: http://trib.in/2pZT07H

• Website: http://www.misterkellyschicago.com

• Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/misterkellyschicago

Happy Medium Ventures is the leading curator and steward of legendary Chicago nightlife venues, London House, Mister Kelly’s, the Happy Medium, and the Rush Street scene, from 1946-1970’s; the epicenter of Chicago’s entertainment scene. Today, Happy Medium Ventures is reviving this bygone era for a new generation of fans through an unprecedented collection of photos, recordings, press clipping. First-person interviews include key players in the Rush Street scene — from celebrity performers at London House, Mister Kelly’s and other Rush Street venues, to the employees behind the scenes, patrons of the nightspots, family and friends. Happy Medium Ventures aims to capture the fun and excitement through a documentary film, a new TV series, vibrant social media and other original content about this captivating chapter of Chicago history.

Daryl Nitz Entertainment is an event-concert production company specializing in shows that celebrate cultural anniversaries and historical recreations. Operating since 2004, with such show as “Judy at Carnegie,” “Voices of Chicago,” “Ladies Sing the Blues: a centennial birthday concert for Billie Holiday,” “It Was a Very Good Year: a centennial birthday concert for Frank Sinatra,” “Above Us Only Sky: John Lennon at 75,” “That’s Amore: a Dean Martin centennial celebration” and many more.

The

Mister Kelly’s team is overwhelmed by the incredibly talented and generous

people that we have met, while creating our archive of the Marienthal Brother’s

legendary nightlife empire. From colorful Rush St. regulars to famous

performers, and everyone in-between, it has been a thrill. One of the most exciting encounters has been

working with the renowned photographer, Art Shay. At the age of 95, Art is truly a legend in

his own time.

Shay began his career as a writer and journalist, but after showing a great eye for capturing images, soon transitioned into a career as a photographer. Based out of Chicago, he became one the nation premier photographers, working for major publications such as Life, Time, and Sport Illustrated. Art Shay photographed everything, from historic moments (1968 Democratic Convention) and iconic personalities (Muhammad Ali, The Rat Pack, President Kennedy), to street photography that captured the everyday life of average Americans. In the process he became one of the most celebrated artists of his medium and a Chicago legend.

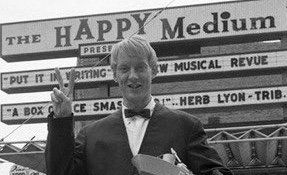

In light of this, we were honored when Mr. Shay was kind enough to donate one of his brilliant works to our project recently. The print is a wonderful slice of Chicago’s Rush Street from the 1960s. The photo was taken outside of The Happy Medium and features actor Tom Williams dressed as a child, holding a toy boat.

Why is a grown man dressed as a child? Why a toy boat? Well, this can be explained. Tom Williams was part of was a comic review, produced by the Marienthal Brothers, called Put it In Writing . In the political satire, Williams plays America’s youngest president (an obvious nod to the newly elected JFK), who still has some childlike features. Put it in Writing would become the biggest play to originate at The Happy Medium and, after a long run in Chicago, it eventually made its way to New York for an off-Broadway production.

We are humbled to receive this generous gift from such a preeminent artist. The photo is a brilliant image of mid-century Chicago history, from one of the men who documented it best. The photo will be cherished and used in our mission to record this unique piece of Chicago and American history. We wish to give a heartfelt thank you to our friend Art Shay, who contributed this beautiful photo to the Mister Kelly’s archive.

Guest Blogger Sam Fazio is a popular Chicago vocalist. He writes about Chicago’s own Mel Tormé, who appeared at Mister Kelly’s many times over the years.

A Kid from the South Side

Born Melvin Howard Tormé in 1925 on the south side to Jewish Russian immigrants, he started singing at a very young age of four with the Coon-Sanders Orchestra, performing at Chicago's Blackhawk restaurant. He continued his early career on radio series, playing drums and writing songs—all before high school graduation.

Mister Kelly's is excited to welcome our newest young guest-blogger, Historian Adam Carston: Simply put, there is American comedy before Richard Pryor, and American comedy after Richard Pryor. With his combination of fearless honesty, provocative language, streetwise cool, and political savvy, he separated himself from other stand-ups. In the process, he also inspired a generation of comedians and cut a new path for them to travel. But Pryor’s famous, challenging persona was not born overnight. It took years of hard work and experience, and a good measure of pain and go-to-hell abandon to fully define it. While there are multiple chapters in Richard Pryor’s emergence as a cultural icon, some key moments that would help shape his career, worldview and revolutionary comedic style took place at none other than Chicago’s entertainment hot spot on the forefront of political change: Mister Kelly’s.